For over 40 years, Diane Horm has researched early childhood education. She joined the University of Oklahoma in 2006, being drawn by Oklahoma’s nationally recognized early childhood programs. Horm has since built a national reputation for her work in Tulsa where she founded the Early Childhood Education Institute (ECEI). Although Horm is retiring this year, her institute is poised to continue her work into the future. In this article, Horm presents the results of her multi-year evaluation of Tulsa’s Educare program.

The Effects of Early Childhood Education in Oklahoma

Oklahoma is considered a leader in early childhood education. In 1998, the state passed legislation requiring its public-school districts to offer free preschool to all four-year old children. Approximately 70% of the state’s four-year-olds currently use this program and only four other states have such extensive programs in place. In 2006, the state legislature extended Oklahoma’s early childhood programs from birth to age three by creating the Oklahoma Early Childhood Program (OECP). Since its inception, over 39,000 children have participated in this program.

But are Oklahoma’s early childhood programs smart investments?

Several renowned multi-decade randomized controlled trials of early childhood education programs find positive outcomes for children suggesting that these programs are worth the investment. Nobel Laureate Economist James Heckman has even shown evidence that the economic return to high-quality preschool programs is greater than investments in remedial academic programs or job training for adolescent and young adult learners.

Yet, some recent studies of larger, scaled-up versions of successful early childhood programs have indicated that initial positive effects on children might fade out. This “fade out” effect means that over time, the outcomes of children who do not attend early childhood programs end up resembling the outcomes of those who do. If early benefits disappear with time, one concern is that investments in early childhood programs are inconsequential over the long run. My team and I wanted to test this possibility in Oklahoma. By using a randomized controlled trial design, we tracked the short- and long-term effects of Tulsa Educare on a group of 75 infants all the way through third grade.

The following are key highlights from our study:

-

Upon reaching kindergarten, Tulsa Educare children showed greater academic gains than children in the control group who did not attend Tulsa Educare.

-

Tulsa Educare children not only entered kindergarten with greater academic skills in math and English language arts but also maintained this advantage over the control group throughout the duration of the study (i.e., through Grade 3).

-

The differences in academic skills between Tulsa Educare children and those in the control group are large (d = 0.60-1.20).

The Educare Model

Educare is a comprehensive early childhood program designed to promote the development and learning of infants, toddlers, and preschool children who are growing up in poverty. Educare started as a single school in Chicago in 2000. It has since expanded into a network of 25 birth-through-age 5 schools. There are Educare programs in Tulsa, Omaha, Seattle, Central Maine, Miami, Phoenix, and Washington D.C. The schools in these areas serve approximately 4,000 young children and their families.

The Educare model has four core features: (1) data utilization, (2) embedded professional development, (3) high-quality teaching practices, and (4) intensive family engagement. Educare schools are built on federal Head Start and Early Head Start standards but go beyond them by including year-round and full-day services; family support staff with reduced caseloads, lead teachers with Bachelor’s degrees, and a research-partnership with local program evaluators. The Educare curriculum is based on developmentally appropriate practices defined by the National Association for the Education of Young Children, and the physical spaces at sites are of high-quality.

Educare in Tulsa opened its first site in 2006. There are now four Tulsa Educare sites serving 434 young children. The average per-child cost is approximately $20,000 for full-day, year-round services. Around 80% of this cost is covered by government funding (e.g. local, state, and federal sources) with the remainder coming from philanthropic sources. The Early Childhood Education Institute at OU-Tulsa is Tulsa Educare’s evaluation partner.

Data and Analysis

In 2010, we began our multi-year randomized controlled trial of Tulsa Educare by selecting 75 children who were 19 months of age or younger. We then randomly assigned 37 of these children to attend Tulsa Educare as infants and the remaining 38 children to a business-as-usual control group. Most families in the control group relied on care at home.

We monitored both groups of children through Grade 3, tracking their early academic performance, behavior, and social emotional development. Children’s academic skills were assessed one-on-one by a trained assessor who was not informed which children were in Tulsa Educare and which were not. Teachers and parents rated social-emotional development. For later assessments during elementary school, we typically had 64 children from the original sample of 75 children. However, Grade 3 occurred during the height of the pandemic, resulting in only 31 children remaining in that year’s sample. When we tested children at the start of kindergarten, there were 19 Tulsa Educare children and 21 control group children in the sample.

Our overall sample is small, so some caution is warranted when generalizing beyond the children in our study. Nevertheless, the random assignment methods that we use allow us to generate credible estimates. Because we followed both the treatment and control groups for 7-8 years, our longitudinal design offers important insight into whether early investments in Tulsa Educare paid off over the long run.

Effects on Kindergarten Readiness

After one year in the program, children randomly assigned to attend Tulsa Educare demonstrated higher oral comprehension than their peers in the control group. They also exhibited fewer parent-reported behavioral problems. At age 3, Tulsa Educare children still showed greater oral comprehension and fewer parent-reported behavioral problems.

By the time the children reached kindergarten (around age 5), we administered a series of assessments to test for kindergarten readiness. On these assessments, Tulsa Educare children showed stronger kindergarten readiness on applied problems, letter-word knowledge, picture vocabulary, receptive vocabulary, and oral comprehension (See Figure 1). For Applied Problems, Tulsa Educare children performed above the national average, which is notable because all of the children in the study were of lower income backgrounds. We also assessed both groups at the end of kindergarten and found that Tulsa Educare children maintained an academic advantage over their control group peers on each assessment.

Effects on Children through Grade 3

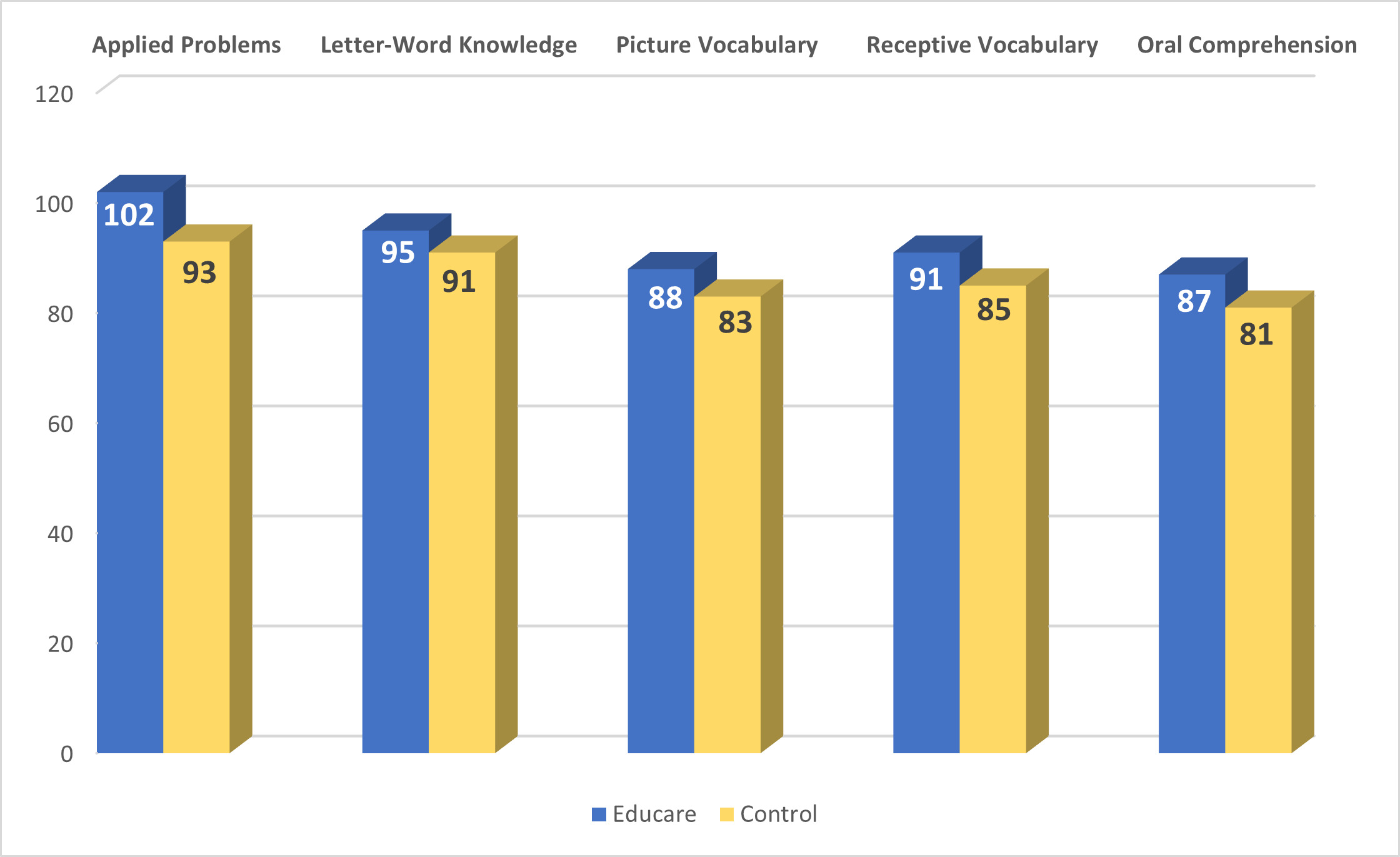

After entering elementary school, Tulsa Educare children scored higher on all academic assessment at all time points from Grade 1 to Grade 3 (See Figure 2). Furthermore, several of the scores recorded by Educare children over time where higher than or close to national averages (i.e., 100).

In the area of social-emotional skills, the two groups of children were rated similarly by their elementary teachers over time. The two groups did not show differential growth rates, so Tulsa Educare appeared to confer an academic advantage to children that was maintained. (Interested readers can read more on these results in the full article)

Our results showed that as infants and preschoolers, Tulsa Educare children developed greater academic skills than children in the control group. These academic gains then persisted through Grade 3 and were large (d = 0.60 to 1.20) in magnitude. Tulsa Educare children’s growth did not slow or fade out, and the control group did not catch up. The overall study provides evidence that high-quality early childhood education produces early academic gains that endure.

Investing in Early Childhood Education

Based on my work over the past four decades, I believe that high-quality infant and toddler programs produce the most significant benefits for children. Educare serves as a prime example of such a program by providing families with full-day services for the entire year, family support staff, and highly trained lead teachers. While the results of our study are from one city, Educare is operational at 25 locations across the United States. The Educare model was also developed from Early Start/Head Start standards, which means that there is a well-established structure in place to expand high-quality early childhood education services to infants and toddlers nationally. However, if we are to bring expand high-quality infant and toddler programs to a larger scale, significant investments will be necessary.

Author Bio

Diane Horm is the George Kaiser Family Foundation (GKFF) Endowed Chair and Professor of Early Childhood Education at the University of Oklahoma. Horm wishes to acknowledge her co-authors Shinyoung Jeon, Moira Clavijo, and Melissa Action who were instrumental to the research presented in this article.