Enrollments in virtual schools have increased in Oklahoma, but the academic performance of students enrolled in these schools remains poor.

It is difficult to believe that the nation’s first fully virtual charter school began operations in Florida over twenty-five years ago. At the time, virtual school entrepreneurs hailed the new model as a revolutionary force that would meet individual learning needs at a lower cost than that of brick-and-mortar schools.

The personalization and flexibility that full-time virtual education might offer is increasingly popular with American families. Leading up to the pandemic, virtual school enrollments had reached 330,000 students in nearly 500 virtual charter and district-run public schools. During the pandemic, virtual school enrollments surged nationally. In Oklahoma, virtual charter schools showed drastic enrollment increases. EPIC charter schools, a virtual school network, became our state’s largest district at the height of the pandemic. Some district-run public schools also established virtual academies to provide students with permanent remote options.

However, the promise of virtual school has been tempered by research showing consistently poor academic outcomes for virtual school students across the United States. In our study, we find similar patterns here in Oklahoma. The academic outcomes of our virtual charter school students compared to their peers are negative, and in most cases, strongly negative. Overall, we observe a seemingly counterintuitive pattern – virtual school enrollments are rising but academic outcomes are poor (listen to a discussion of the study’s results here).

Data and Analysis

For our analysis, we used administrative data collected by the Oklahoma State Department of Education for all tested students in the state from 2017 to 2019. We first identified students (Grades 3-8) who switched between district-run public and virtual charter schools between school years, and then look at how the same student performs when attending a district-run public school versus when he/she attends a virtual charter school. While this statistical approach can generate credible estimates of student performance, students who switch schools between years may also be those who face physical health problems, mental health challenges, family disruptions, or issues that drive them to fully virtual schools when academics are less of a priority. If so, poor results for students who switch in and out of virtual charter schools might represent personal difficulties rather than anything negative about fully virtual school itself. So we generate additional evidence by comparing the results of students in Grades 3 to 8 who remained in the same school for three consecutive years (2017-2019). These comparisons account for student grade level, race/ethnicity, free- and -reduced priced lunch status, IEP status, English language learner status, prior individual achievement, and school year. We also analyze the high school level by comparing achievement between virtual charter and district-run public school students in 11th grade. These comparisons account for the prior year’s achievement in 10th grade along with the other sociodemographic characteristics listed above.

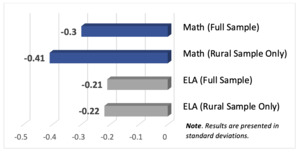

We examined results for students from rural areas as well. About 61% of virtual charter school students in Oklahoma were previously enrolled in district-run public schools located in rural areas, so knowing how this specific subset of students is faring in virtual charter schools is imperative.

Results

Based on over 800,000 test scores, students in the full sample show much lower scores in English language arts (ELA) (-0.21 SD) and math (-0.30 SD) when they are attending a virtual charter school compared to when these same students are enrolled in a district-run public school. To put these findings into perspective, researchers estimate that average annual achievement growth is 0.31 standard deviations in ELA and 0.42 standard deviations in math for students in Grades 3 to 8. By using these annual growth projections, our negative results correspond to about two-thirds of an academic year of learning in ELA and more than two-thirds of an academic year in math. In the sub-sample of students from rural areas, virtual school students show similarly low scores in ELA (-0.22 SD) and math (-0.41 SD). Figure 1 presents results for both the full and rural samples.

The results above show how the same student performs in a virtual charter school compared to when he/she is attending a district-run public school. One potential critique of this analysis is that it focuses on students who switch schools between years, but switching schools could be emblematic of physical and mental health problems, family disruption, or other shocks in the life of a student. The poor results for virtual school students could be attributable to challenges in the lives of students who tend to opt for virtual schooling rather than anything negative about fully virtual learning itself. So, we also examined students who remain in virtual charter schools for three consecutive years to see if greater school consistency would be associated with stronger achievement in the virtual charter school sector. Unfortunately, this was not the case.

Among students who remain in the same school for three academic years, virtual charter school students show negative scores in math (-0.41 standard deviations) and ELA (-0.22 standard deviations) when compared to their peers attending the same district-run public schools. These estimates are presented in Figure 2 below. According to annual academic growth estimates, these results correspond to approximately three quarters of an academic year in ELA and about an entire academic year in math.

In high school, virtual charter school students do not underperform their peers in district-run public schools as much as they do during Grades 3-8. Nevertheless, results for virtual charter school students remain negative. In Figure 3, results show stronger negative associations in math than in ELA for virtual charter school students. Because annual academic growth is slower in high school, estimates correspond to about 85% of a year of learning in math during eleventh grade. The smaller negative associations for ELA are not statistically significant. They show the smallest difference between virtual charter school students and those in district-run public schools.

Questions for Policy

Our results are derived from a rigorous multi-year analysis of a large student sample in Oklahoma. The findings are mostly consistent across different statistical models. Still, we cannot say that fully virtual schooling causes learning loss. Students who decide to enroll in virtual charter schools may be atypical in ways (e.g., mental and physical health challenges, family disruption, and complex behavioral needs) that cannot be accounted for with the administrative data that we analyzed. If so, the negative performance of virtual charter school students may be at least partly attributable to the types of students who choose virtual charter schools.

Looking back to the opening of the first fully virtual schools more than twenty-five years ago, original hopes for student learning in these schools have not materialized. Critics contend that virtual schools are likely to be ineffective because they require extraordinary levels of parent monitoring and engagement as well as an uncommon ability for a student to learn independently. Virtual schools might also struggle to replicate collaborative learning, group work, and peer interactions that are thought to foster learning in traditional classrooms. Experiences with remote learning during the pandemic seem to be casting more doubt on the effectiveness of fully virtual school.

The Oklahoma State Department of Education cautions families who are considering full-time virtual options, stating that virtual schools are not for every student and that they require both student independence and regular parental monitoring. It is unclear if this advice is reaching families or if it is adequately preparing them for what to expect. Even though virtual school leaders may still find a way to make these models work better for students in the future, additional work is probably needed to identify the conditions necessary for optimal learning in virtual schools.

Author Bios

Daniel Hamlin is Professor of Education Policy and Research Director of the Leadership and Policy Center for Thriving Schools and Communities (THRIVE) at the University of Oklahoma.

Curt Adams is Professor of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at the University of Oklahoma.

Beulah Adigun is Professor of Educational Leadership at Oklahoma State University.

.png)

.png)